Revolt of the Comuneros

If kings and queens were the rock stars of 16th-century Europe, Spain in the early 1510s was their Madison Square Garden.

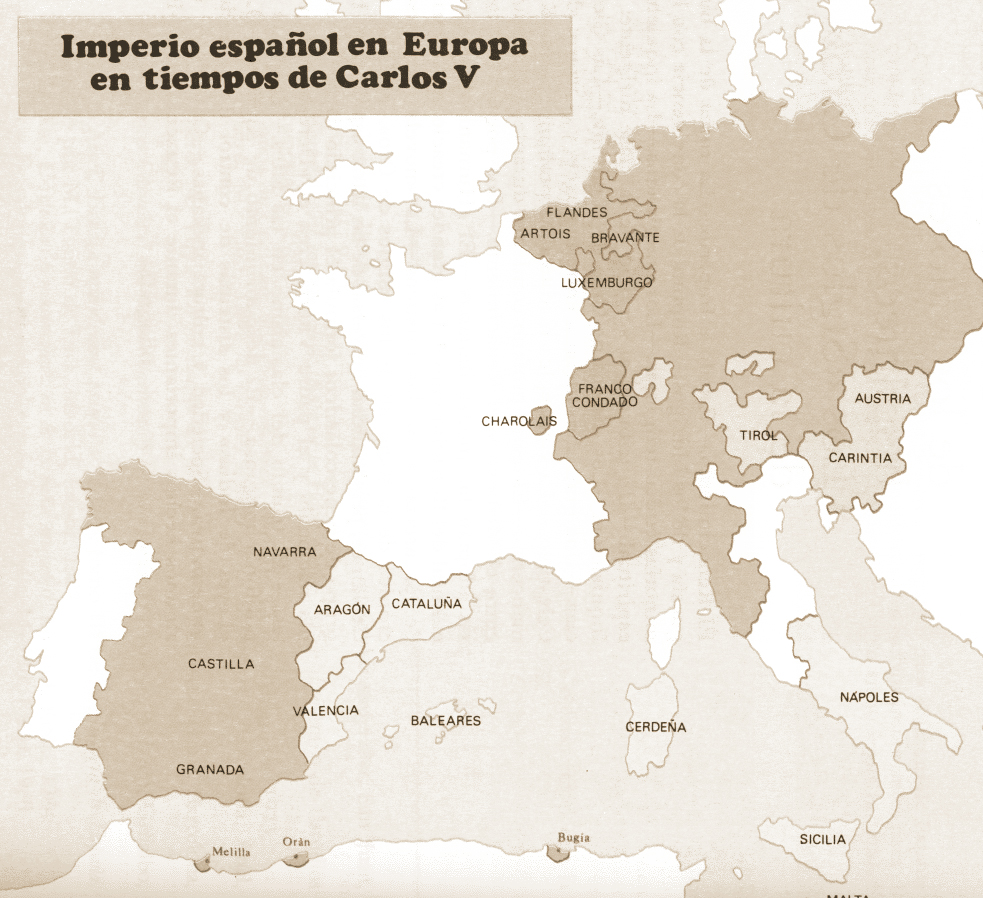

Not only did Spanish culture rest on an unflinching adoration for their monarchy, they also had some of the most notable monarchs in Europe. And the king of kings in all those monarchies was a man simply called Charles. Son of a Spanish princess and of a Dutch king, he became ruler of Europe's three main dynasties - the Hapsburg Monarchy, the Duchy of Burgundy; and the Crown of Castile-Leon and Aragon.

He became known as Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and he put Spain's love for kings to the test.

Ostensibly, he allowed Spain to thrive. His reign meant that Spain became part of the biggest Empire in European history. It included his three major kingdoms, the Americas which Spain had just begun to conquer, as well as the African territories, lands which they had coveted for many years. Clearly, Spanish affairs were taking place very far away from the core of Spain.

But that was a problem. Whilst acquiring new territories was highly prestigious for the monarchs and the courts, the lower classes and peasants – the ones who were paying for wars – received no direct benefit from them. All they knew about Charles V was:

- He barely had any knowledge of the Spanish language.

- He was more concerned with non-Spanish affairs than anything else

- He treated Spain as insignificant in his global outlook (though economically it still was – compared to other kingdoms he was in charge of).

In fact, either because he was a visionary or a careless despot, he began treating both Castile and Aragon as the same kingdom, which nobody else in Spain agreed with.

In short, he had completely lost touch with his people.

The Comuneros Stir

The division between historical-enemies-turned-best-friends Castile and Aragon was always a significant feature in Spain’s history. Each kingdom was used to being treated as its own entity. But Charles V abused this tradition. He decided to live in Castile whilst forcing the kingdom to pay for most of the wars happening elsewhere in Europe. For Spain being united with many of its previous adversaries was a hefty sum to pay.

In early 1520 things reached boiling point. Charles V left for Brussels to attend his other affairs, leaving Castile in the hands of a Dutch Bishop -- Adrian of Utretch. But this pushed the peoples’ patience to breaking point. It was one thing to be ruled by a Dutchman who was also grandson of Ferdinand of Aragon and son of a Castilian princess. But to be left in the hands of a complete stranger who seemed to have little idea of what Spain was, was quite another.

Adrian didn't see the problem here and did what Bishops did best back then: favor the economic interest of the nobles over that of the peasants.

The people had had enough. Soon rebellion sprang up all over Spain.

The Comuneros Revolt

In February, Toledo kicked their Corregidor Real (something like a general manager) out and became an independent community. Other cities began to follow suit. The men behind these people where called the Comuneros (both because they belonged to the lower Spanish classes and were therefore "common" and also because they created "communities" regardless of the pre-existing borders). Soon many patriotic nobles decided to join them.

With the coming of the summer in Spain, Adrian had resorted to violence to quell these comuneros revolts (because this is what rulers did with popular rebellions back then), which in turn made the Comuneros join tighter and create an armed Comunero force. Adrian, who may have been despotic and politically blind, was not stupid and fled the country in September. The Comuneros had accumulated such momentum, though, that they were not about to stop there. They went for the next authority after Adrian: Charles V himself.

By November, the rebellion had escalated into an all-out revolution. It was so organised that the Comuneros already knew exactly what they wanted. They wanted to have Charles' mother, Joan (nicknamed 'La Loca', 'The Mad', because the involuntary confinement Charles had subjected her to had driven her to develop a mental depression) named queen. They already held Tordesillas, the province where she was held captive. If that couldn't happen, they wanted Charles V to return and do his job as a king -- to live in Castile, to fill out his high offices with Castilians and to marry.

The Final Confrontation

Charles paid very little attention to the demands that originated in the comuneros revolts (in his defence, though, it must be said that ruling three kingdoms is not an easy job) but with the revolutions fuelled by countryside peasants, a lot of the rural nobility had no problem siding with him and fighting off the rebels. But when Queen Joan was taken from the Comuneros they retaliated with a crushing victory in the battle of Torrelobaton in February 1521.

In April 1521, the Comuneros lost all hope when they were defeated in the battle of Villalar.

This doesn't mean it was for naught. Charles V considered that events like these were too serious to ignore and started to spend more time in Spain, learned Spanish and named Castilians for his high office. He got married and had children. Maybe he would have dropped his economic favour to the nobles, too, but that was too much to ask for the 1520's.

Bishop Adrian of Utretch, though, continued to have bad luck for the rest of his life. He was elected pope and died a year later.